You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Interviews’ category.

Shirley Raye Redmond has written books about bunyips, mermaids, the Jersey Devil, and Richard Branson. (Quiz: Which one of these things does not belong in KidHaven’s Monsters series?) Her most recent book is Norse Mythology (Gale Cengage 2012). Here, Shirley Raye answers a few questions about her prolific output, the business of writing nonfiction for kids, and, as always, the Profesor’s question.

Shirley Raye Redmond has written books about bunyips, mermaids, the Jersey Devil, and Richard Branson. (Quiz: Which one of these things does not belong in KidHaven’s Monsters series?) Her most recent book is Norse Mythology (Gale Cengage 2012). Here, Shirley Raye answers a few questions about her prolific output, the business of writing nonfiction for kids, and, as always, the Profesor’s question.

fiction, but have you always wanted to write nonfiction? Your output is astounding–what keeps you going from project to project?

but you probably have a favorite topic or area of research that interests you. What sort of book do you most enjoy writing?

but you probably have a favorite topic or area of research that interests you. What sort of book do you most enjoy writing?

If readers visit my website at www.shirleyrayeredmond.comthey’ll get an idea of the sort of topics I’m interested in.

kids?

Thank you, Shirley Raye!

Shirley Raye has very kindly offered to give away a copy of Fairies! and Oak Island Treasure Pit. To win one of these wonderful books, leave a comment telling me your favorite work of children’s nonfiction. Winners will be drawn randomly from all comments entered before midnight on October 26, 2012. That’s this year, folks, so don’t wait too long.

This is part of a series of interviews with New Mexico children’s writers to celebrate the 2012 centennial. (1)

Lauren Bjorkman (2)is the author of My Invented Life (Henry Holt , 2009), a YA novel that takes on sibling relationships, sexual identity, and Shakespeare, all through the voice of cynical-yet-daydreaming teen theatre geek Roz. PW called it “fun, thought-provoking reading,” and I have to agree. Welcome, Lauren!

Lauren Bjorkman (2)is the author of My Invented Life (Henry Holt , 2009), a YA novel that takes on sibling relationships, sexual identity, and Shakespeare, all through the voice of cynical-yet-daydreaming teen theatre geek Roz. PW called it “fun, thought-provoking reading,” and I have to agree. Welcome, Lauren!

Roz has such a strong voice, and she’s such a believable mix of self-awareness and denial. How did you develop her voice in writing My Invented Life?

I started with a picture in my mind—a big, adorable dog that wants to be loved, but doesn’t know how to behave around people. To that, I added some observations I’d made of a young woman in my hometown, a talented actress with a big heart and boundless energy. Once Roz came alive for me, everything I wrote went through the Roz-o-matic filter—would Roz do this? Would Roz say that? It was great fun to create someone so unlike myself.

The plot of My Invented Life models the play, As You Like It, that the theatre geeks are practicing. How did that come about? Were you planning from the start to use Shakespeare? If you had to introduce Shakespeare to teens using a different play, which would it be?

I started with my sisters, and the secret that divides them. Then I fleshed out my characters and designed a rudimentary plot. When I shared my thoughts with my critique group, one talented writer said, “Your plot sounds like a Shakespearean play, where everyone is pretending to be someone else. I’d seen As You Like It in high school, and re-read it. That gave me an insight—Roz had all the hallmarks of an actress. So I transformed her into one.

First off, I’m no expert on education. But I remember my own experience struggling with Shakespeare in high school. Hating it, to be honest. So here are my recommendations based on n=1.

- Read the play aloud in class, stopping to interpret the language at every turn. Switch roles, so everyone gets a turn to read.

- Let your students watch a theatrical or movie version of the play.

- Romeo and Juliet is a good choice because it has both romance and swordplay, and therefore broad appeal.

Stories like Roz’s let readers into the mind of someone who is questioning all kinds of things: sexuality, loyalty, friendship, self-worth. What do you hope readers will take away from reading My Invented Life and other books with similar themes?

For me, reading is often about taking a look at life through new eyes (while being entertained, of course!). Who in the story can I identify with most? What would I do in the main character’s shoes? I want my readers to be surprised, and, if they don’t quite fit in, to feel less alone. My story is celebration of our differences.

In my next novel, Miss Fortune Cookie, about a teen advice blooger, my characters are not LGBT. Still, when a gay hate group pickets their school, they organize an event—a sort of modern day love-in/dance party—to counter-act the hate.

I heard you speak at a bookstore event with Malinda Lo, Alexandra Diaz, Megan Frazer, and Kristin Cronn-Mills on LGTBQ youth literature (3). That was 2010; what do you think of the state of things today? What are some of your favorite recent books for teens on LGTBQ issues?

What a fun event! Sadly, the issues around bullying of LGBTQ teens haven’t diminished, but the number of teen LGBTQ novels published each year continues to grow. More schools have Gay-Straight Alliances than ever before. I adore the It Gets Better Project , and feel optimistic about the future.

I haven’t kept up with my TBR this year because of building a house, and then moving in! That said, I managed to read and fall in love with Will Grayson Will Grayson.

Kirstin Cronn-Mills has a new novel about a trans character coming out in October, Beautiful Music for Ugly Children–Love, transition, violence—mix with music, and broadcast on the radio. Not your typical teenage life.

Malinda Lo’s new YA science-fiction thriller called Adaptation will be released in September. Reese can’t remember anything from the time between the accident and the day she woke up almost a month later. She only knows one thing: She’s different now.

What is the best part about writing for teens? Have you heard anything from a teen reader that really made your day?

For me, it’s all about fame and fortune. Just kidding! The best part is making connections with teens. It’s great when someone is crazy about my book, of course, but sometimes a teen just needs someone to talk to or take an interest in his or her writing. I love that part too.

Here are a couple fave reactions: One reader wrote that she sighed and hugged my book after finishing it, like it had become a friend. Another chose my My Invented Life as the next Great American Novel for a class assignment, which cracked me up, and made my day.

The professor’s question (in honor of Vaunda Nelson’s great-uncle, who started a bookstore with fivebooks): If you had to start a bookstore with just fivebooks, which five would you choose? These aren’t necessarily your five favorite desert island books, but the five you most want to share with the world.

Hard question! I’m kind of fickle. My favorite books change all the time, depending on what I’m reading.

So I’ll recommend my favorite classics, plus one amazing graphic novel:

To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee

Emma by Jane Austen

East of Eden by John Steinbeck

Jane Eyre by Charlotte Bronte

American Born Chinese by Gene Luen Yang

Are there any excellent Shakespearean curses that didn’t make it into My Invented Life?

Go read a book, thou infectious clapper-clawed pignut!

Good advice! Thank you, Lauren, for this interview!

1. For more interviews with NM children’s writers, go here.

2. Visit Lauren’s website.

3. Malinda Lo. Alexandra Diaz. Megan Frazer. Kristin Cronn-Mills.

This is part of a series of interviews with New Mexico children’s writers in honor of the 2012 centennial.

Kersten Hamilton writes picture books, middle grade, and YA. Her most recent book is In the Forests of the Night (Clarion, 2011), number two in her series, The Goblin Wars. A brief encapsulation: Irish mythology lands smack in the middle of the present day, and Teagan Wylltson is one of YA fantasy’s smartest heroines.

Kersten Hamilton writes picture books, middle grade, and YA. Her most recent book is In the Forests of the Night (Clarion, 2011), number two in her series, The Goblin Wars. A brief encapsulation: Irish mythology lands smack in the middle of the present day, and Teagan Wylltson is one of YA fantasy’s smartest heroines.

Welcome, Kersten! You can put your wings over there in the corner.

Your book Police Officers on Patrol is a great example of a picture book with rhythm, a nice balance of variation and repetition, and an economy of wording that gets the story across and gives plenty of room to let the illustrations do their work. What are your thoughts on picture book creation, and do you secretly long for the days of yore when you could write a 3000-word picture book and your friends at SCBWI meetings wouldn’t laugh?

I’m so glad you like Police Officers on Patrol! I loved writing that book. I pitched it to my publisher as “nitty-gritty for the itty bitty”, a cop show format of three storylines all resolved in 138 words.

pitched it to my publisher as “nitty-gritty for the itty bitty”, a cop show format of three storylines all resolved in 138 words.

Writing picture books is like blazing a path through the wilderness that stretches between oral tradition and the written word. Your audience is comprised of sophisticated thinkers and story connoisseurs who lack only reading skills. Learning to track those letters across the page is one of the most difficult things they will ever do. Picture book writers have the ability to make that work worthwhile.

Whenever I sell a picture book, my novelist self sends my picture book self a box of truffles and congratulations. Hurray! (I tell myself) This book will capture wild toddlers and transform them into civilized readers!

I’ll answer the 3000 word picture book issue with your next question…

How do you whittle down the text of a picture book, knowing that it has to be a certain length? Or is it less a whittling process than a building process?

I’m a whittle–upper. When I am writing for the very young, I use repetition, rhythm and meter and that naturally limits the length of the book.

But when I picture storybooks, they sometimes bulge beyond their bounds. I had a lovely 2000 word picture book that was simply too long to sell. When I sat down to make it publishable I accidentally added 70,000 words. Since I am a whittle-upper, I couldn’t take them out again. I had to sell it as a YA novel. (So that’s the secret…)

Who are some of your favorite writers, both in the fantasy genre and in other genres?

I indulge in time travel. It says so right on the front of my business card: Kersten Hamilton, Author–Adventurer. Time Travel, Goblin Hunting and Paranormal Investigations. I can only travel into the future at one second per second, but the past is an open book. I’ve met people like Shakespeare, George MacDonald, Charles Williams…there is always someone new and exciting to discover in the past.

If you answered Tolkien or Lewis as part of your answer to the last question, you anticipated this one: Tolkien and Lewis loom over the landscape of quest fantasy, as well as that of certain domains of literary and historical scholarship. What it is about their work that still holds sway over readers today?

Well, I didn’t list them but I love them both.(Half-credit for The Chained Library. Darn.)What still holds sway over readers? They baptized imaginations. On purpose. What does that mean? Kerry L. Dearborn writes of C.S. Lewis’ own experience of having his imagination baptized by a book: “Rather than leading him into an escape from reality, it washed away blinding scales and gave him a new vision of reality. Rather than providing mere ornamentation for a life which for him held no lasting significance, it led him to sense the enduring goodness at the heart of all things. Instead of feeding his sense of being alone in the vastness of the universe, Phantastes began to draw him out of himself to feel a fundamental connection with all of creation.”

I love George MacDonald more than I love Lewis and Tolkien put together.

Lewis’s wrote: “I know nothing that gives me such a feeling of spiritual healing of being washed as to read MacDonald.”

Yeah. Me, too.

Suddenly I want to rush out and read The Princess and the Goblin. Wait a second…goblins…

When you let out your inner Inkie and attend MythCon, are you there as a reader and a writer? That may sound a little dumb, but I mean, do you go specifically thinking that you’ll get some nuggets or research for a project?

Both! I went to mingle and marvel at professors and other folk who love the same things I love—and are much, much smarter than I am. As I wandered the hotel halls, I had a certain project in mind that I am not nearly smart enough and certainly not educated enough to write. I’m going to write it anyway.

Your teen novels are based on Irish mythology. Why Irish?

Because it suits my pseudo Celtic worldview: I do not separate the natural from the supernatural.

What do you think of the myth craze in YA fiction these days?

I enjoy it…when the books are well thought out and executed. And hate it when they are tripe.

Do you wonder if readers go and read the original myths after reading a fictionalized version? How can I say this without sounding like, well, a librarian: Do you think that readers should read the originals as well?

I know that some of my readers do, and it thrills me. I am working to connect them with the flow of literature through time. I want them thinking, hmmm. Why did she choose this instead of that? Why did she change this little piece?

My end goal to inspire future writers to who go on to write wonderful books…that I then get to read.

The professor’s question (in honor of Vaunda Nelson’s bookselling great-uncle): If you had to start a bookstore with 5 books, what would they be? These aren’t necessarily your 5 favorite desert-island-style books, but the 5 books you’d most like the world to read.

Considering my answer to the last question, I think I’d better choose books that have spawned many, many stories in the past—because they would have to seed a whole bookstore of books for me to read!

1. The Bible. The single most influential book in Western literature. You won’t understand Chaucer or Spencer or Tolkien without it.

2. A collection of Fairy Tales from every tribe and nation. We gather our cultural wisdom and preserve it in fairy tales.

3. A collection Myths and Legends from every people and place. We explore our beliefs about ourselves and our environment in myth and legend.

4. The Jungle Book by Kipling. I just like Kipling. Have you ever tried it?

5. Where the Wild Things Are – what other picture book would be so at home on an imaginary island?

Since this is part of a series on NM writers, what are some of your favorite books set in NM? Favorite NM writers, children’s or adult?

I’m going to stick to dead people because we have many wonderful writers living in and writing about NM today. I don’t want to be embarrassed by forgetting anyone.

The top of my list would be Tony Hillerman. Tony was one of the greatest gentlemen I have ever had the honor to know. I want to be him when I grow up.

Jack Williamson. The Dean of Science Fiction. He came to NM on a covered wagon, and took his readers on spaceships to the stars!

Lew Wallace. Okay, Ben Hur wasn’t that great, but how many states can claim that their Governor neglected his duties in order to write a best selling novel while in office? Yep. We are the only one.

You are known for saying incredibly intelligent things in interviews. Say something incredibly intelligent about, I don’t know, Aristotle.

Gah! You are tweaking me because I accused Aristotle of dabbling his skeletal fingers in our YA literature on Uma’s blog, aren’t you? (Important note: I do not tweak my guests, virtual or otherwise.)

Plus, I have never heard anyone claim that I say intelligent things in interviews. Mostly I hear them say, “Er…you promised me that interview by 5 p.m. today. It’s 4:45. Have you started on it yet?”

Thank you for having me on your blog today, Rebecca!

Thanks for being here! Read Uma Krishnaswami’s interview with Kersten here, and another interview with Kersten at The Enchanted Inkpot (where you will see more incredibly intelligent responses).

Image of Kersten Hamilton courtesy of Rio Rancho Public Library and ALA Graphics (and, of course, Kersten Hamilton).

This is part of a series of interviews with New Mexico children’s writers–and now illustrators–in celebration of the 2012 state centennial.

Lesson for the day, and possibly for all time: you never know what you’ll get unless you ask. In that spirit, I’m very happy to present an interview with an artist I like to call the Queen of Toddler Time, Jan Thomas.  Jan’s books are hardly ever on the shelf at my library, and when they do come back, you can tell they’ve been read within an inch of their lives. With bright colors and simple layouts, foolish yet earnest characters, and interactive fun, these are the books that will bring 2022’s teens furtively into the picture book section and send them giggling into a corner, the way they do today with The Stinky Cheese Man. Welcome, Jan!

Jan’s books are hardly ever on the shelf at my library, and when they do come back, you can tell they’ve been read within an inch of their lives. With bright colors and simple layouts, foolish yet earnest characters, and interactive fun, these are the books that will bring 2022’s teens furtively into the picture book section and send them giggling into a corner, the way they do today with The Stinky Cheese Man. Welcome, Jan!

I know next to nothing about visual art (forgive me). Can you describe your style and media to me, so that I don’t make some embarrasing gaffe?

I start off by doing lots and lots of sketches. (I have stacks of sketchbooks piled high in my studio..) Then I take the sketches that look like they might have potential and redraw them several times (ten times seems to be the magic number). Next I scan them into my computer and do more finished drawings using a drawing program (Adobe Illustrator). I send the files off to my editor and she makes comments and we go though many revisions that way.

I do love the saturated colors that you can get with digital art. It makes every so super-cartoony.

Like Mo Willems’s Elephant and Piggie, your characters have a sort of green-screen existence: they might be anywhere, with those solid color backgrounds. Is it a purposeful choice, to allow readers to imagine their own settings, or to concentrate on the characters more?

I have a real ‘less is more’ approach to my books. My goal is to create books that are light and fun and not at all intimidating. I’m striving for a toy-like quality that hopefully will make kids think reading=fun. I also like the idea of using my books for story time and the green-screen look works well for that. I really emphasize facial expressions and I think much of that emphasis would be lost if I had too much detail. I do appreciate children’s books that have great amounts of detail, but that’s not what I’m after.

I have a real ‘less is more’ approach to my books. My goal is to create books that are light and fun and not at all intimidating. I’m striving for a toy-like quality that hopefully will make kids think reading=fun. I also like the idea of using my books for story time and the green-screen look works well for that. I really emphasize facial expressions and I think much of that emphasis would be lost if I had too much detail. I do appreciate children’s books that have great amounts of detail, but that’s not what I’m after.

It wasn’t done in a laboratory or anything, but I have evidence that your observation about storytime books is absolutely true. It really draws kids into the action.

It’s easy to recognize a Jan Thomas book at a hundred paces, but I bet it’s not easy to come up with such a distinctive style. How did you develop the JT look?

I’m not exactly sure how I developed it, but I can’t seem to undevelop it. I think I’ve been drawing this way since I was 3 years old.

If it ain’t broke…

What’s your background or training?

I studied graphic arts at Oregon State University. I worked as an illustrator at the NM Natural History Museum and as a cartographer and graphic artist at NM Tech. I also did a syndicated comic strip with my husband for a while. I think doing the comic strip made me focus on simplifying things and stripping things down to the most essential parts.

The choreographer Twyla Tharp called art “a vast democracy of habit.” I love this because it points out the side of art that people

The choreographer Twyla Tharp called art “a vast democracy of habit.” I love this because it points out the side of art that people

(non-artists, let’s say) tend to overlook: at some point, you have to sit down and actually do the thing. What are some important features of your creative process?

I like going on long walks or runs or bike rides when I’m in the idea stage of a book. It may seen like I’m goofing off, but the ideas flow much more effortlessly than when I’m sitting at my desk. When I’m in the drawing stage, I listen to music. I tend to stay in my seat much longer if there are great songs that I want to hear.

Working in picture books is truly interdisciplinary, since a picture

book has to be a perfect match of text and image. What are your thoughts on picture book creation? Favorite picture books & creators?

I guess I’m drawn to books that are very simple but have great (often interactive) concepts. Some of my favorite picture books are: THE MONSTER AT THE END OF THIS BOOK, PRESS HERE, TICKLE THE DUCK, I WANT MY HAT BACK, CAPS FOR SALE and BARK GEORGE.

Since this is part of a series on New Mexico children’s writers (and now illustrators), do you have any favorite books set in New Mexico?

I think Tony Hillerman books made me move to New Mexico (I LOVED them.). Neecy Twinem’s picture book E IS FOR ENCHANTMENT is wonderful too.

The professor’s question (in honor of Vaunda Nelson’s great-uncle): If you were to start a bookstore with 5 books, which would you choose? They aren’t necessarily going to be your five favorite, desert-island-style books, but the 5 books that you would most want to spread to the world.

The professor’s question (in honor of Vaunda Nelson’s great-uncle): If you were to start a bookstore with 5 books, which would you choose? They aren’t necessarily going to be your five favorite, desert-island-style books, but the 5 books that you would most want to spread to the world.

It would have to be 5 Pippi Longstocking books. I read Pippi books over and over as a child. She is my hero.

Suddenly I want nothing more than to see a Jan Thomas Pippi. I liked Lauren Child’s, but I have the feeling that yours would show the appropriate amount of insanity.

You’re a SCBWI-NM success story. Do you have words of hope, inspiration, or warning for the rest of us?

I guess . . . keep plugging away . . . and cross your fingers! (It was pure luck that I submitted my first book to the right editor at the right time.)

When is the new Jan Thomas book “Daisy the Librarian Cow” coming out? Will it come out any faster if I give you some Pringles?

Pringles??!!! I’ll get get cracking on the book right away!

They’re in the mail.

Thank you so much, Jan!

Visit Jan’s website here. Read her books anywhere.

For a wonderful in-depth interview, read 7-Imp’s interview with Jan.

This is the fourth in a series of interviews with children’s writers in New Mexico for the state centennial.

Katherine B. Hauth is the author, most recently, of What’s for Dinner? Quirky, Squirmy Poems from the Animal World (Charlesbridge, 2011, illustrated by David Clark). If you’ve always suspected that nature isn’t all lions lying down with lambs, this is the volume of poetry for you. Its 29 poems, with titles like “Four Ways to Catch a Seal,” cover the range of animal eating habits, and let’s just say that it’s not all vegetarian. Katherine has included a section in the back explaining some of the terminology in the poems, as well as a brief note about the subjects of each poem for young zoologists. What’s for Dinner? was a Junior Library Guild selection, a 2011 NM Book Award for juvenile literature, an Outstanding Science Trade Book selection by the National Science Teachers Council and is on the master list for the Lee Bennett Hopkins Penn State Poetry Award. Welcome, Katherine. On to the questions.

One of the questions I have about poetry is this: what, exactly, is it? This isn’t the hopeless or meanspirited question that it seems to be. I’m always interested in what poets have to say about their forms, because poetry is such a rich area of literature, and I think it’s often misunderstood (maybe just by me). When you’re not writing in the kind of strict forms that we study in school, how do you know that what you’re writing is poetry? What separates poetry from short snatches of prose?

I’ve been thinking about this lately as prose poems and books in verse grow more dominant, and the lines between them become less distinct. With today’s more flexible boundaries, I’m afraid it’s easier for a poet to lose the carefulness, the edge, and for a would-be poet to never achieve it.

more dominant, and the lines between them become less distinct. With today’s more flexible boundaries, I’m afraid it’s easier for a poet to lose the carefulness, the edge, and for a would-be poet to never achieve it.

Quoting a friend, “Poetry is a lot like pornography. I can’t describe it, but I know it when I see it.

Classic! I’ll bet you don’t say that to kids.

I found a quote from Neil Philip the other day that makes a lot of sense to me. He says, “Some would argue that the very notion of poetry for children is a nonsense. Yet there is a recognisable tradition of children’s verse. It is, most crucially, a tradition of immediate apprehension. There is in the best children’s poetry a sense of the world being seen as for the first time, and of language being plucked from the air to describe it. This does not necessarily mean that children’s poems are ‘simple’ in any reductive sense. I would argue that no poem can be called a poem that does not have at its heart some unknowable mystery.” I’ve added italics to those phrases that help to answer that question, not just about children’s poetry, but poetry in general.

You write about the natural world in a fun and, dare I say, quirky way that kids respond to. What subjects do you want to explore in poetry in your future work?

Most of what I write springs from natural history experiences or facts that won’t leave me until I do something with them. I’ve barely begun to explore animal behavior. I think there also may be geologic forces to be reckoned with.

New Mexico’s a good place for that!

The poems in What’s for Dinner? vary in length, style, & form. There’s haiku, concrete poetry, rhyme, and free verse. How do you match form to content?

Form and poem length seem to follow rather naturally from the subject. Four Ways to Catch a Seal wanted to be four distinct stanzas. Since that’s traditional form, it follows that I’d use uppercase to start each line and I’d have a regular rhyming pattern. If a poem is quite short, I’ll often see if it can be a haiku. A more complex subject demands more length.

Since a picture is said to be “worth a thousand words,” I enjoy using shape (concrete poetry) to enhance a poem’s action as in Fast Food when a snake is free falling through the air between two hawks. In Not a Banana, I use an offset line for the banana slugs’ escape onto a separate page. Especially for children’s poems, I like to play with shape.

As I start thinking about a subject and how to describe it, rhyming and alliterative words usually present themselves. I consider appropriate similes, metaphors, repetition, and patterns. For Cowgirl Spider, I fairly quickly had the words and shape that became the last four lines (two split lines): Fancy twirler, // tricky spinner, // spider cowgirl // catches dinner. // I knew there would be a poem, but the first portion took quite a while to get just right.

It may be poetry, but it’s also science. How much research goes into one of your poems?

Since I’m not an expert in anything, but am fond of exploring things I don’t know, I often need to do quite a bit of research. I may have a poem rip-roaring along only to find that my assumption is wrong. When I saw hawks passing a snake between them mid-air I was sure it was a parent and a well-grown youngster. I wrote it that way. Before presenting the poem for publication, however, I needed professional confirmation. I didn’t get it. I needed to change the players in the poem. Usually an error can’t be changed simply by word replacement because rhythm or rhyme becomes adversely affected.

Fashioning a scientific subject in poetic form can be tricky. One of the first editorial comments on poems for my What’s for Dinner? . . . collection was, “The science pushes too hard upon the poetry.” I’m so grateful for that feedback and have been grappling with the dichotomy between poetic and scientific language ever since. In a separate work, every time I was satisfied with the poetry, my technical resource would advise me where and how it misrepresented science—within my subject’s focus or beyond. When I’d get the science absolutely right, the poetic feeling was gone. I was like a pendulum going back and forth between my technical expert and my critique group to achieve the right balance.

What’s one of the best stories from your visits to places like Africa ?

The most interesting/ unexpected experience turned out to be an August 1991 trip down theDanube. I was looking forward to a beautiful and idyllic cruise betweenVienna and Istanbul—with no idea that there would be a coup in Russia while we were on Russian ships. But that was after the flood.

The river was running too high for us to clear the Tito Bridge so we couldn’t leave Budapest as planned. The next day looked possible for the bridge, but all Danube traffic was stopped due to security for the pope’s arrival in Budapest. Jolted awake by a PA announcement in the middle of the night, we were told there would be an “immediate passenger inspection” and strongly advised to “look as much like our passport photos as possible.” The next day, other than a police patrol boat, ours was the only vessel on the river—a rather eerie feeling.

At the Tito Bridge only five inches separated our ship from the grating sound of miscalculation. The rest should have been clear sailing, but complacency was soon shattered by the whispers, “Gorbachev resigned.” Word spread among passengers with the feeling that he had been killed. Due to mountainous terrain, CNN International was not reaching the ship. Only Russian radio. What would be true, what false, of anything we heard? We had passed bombings in Vukovar and attack dogs being trained in Bratislava. Would war break out? What would the Russians do with us?

The professionals on the boat kept things running smoothly with most of our scheduled historical and cultural side trips. For a few hours, we enjoyed Romanian food, lively music, and dance on an upper floor of a hotel. But the program ended, the elevator descended to a drab lobby, and reality. A desk clerk who spoke English told us that the KGB, the army, and the Vice President had been involved in the coup. Gorbachev was under house arrest at his Crimean vacation house—as far as he knew. The papers were a day old. We traveled uneasily between history and an uncertain present.

When we transferred to a second Russian ship to transit the Black Sea to Istanbul, we didn’t set foot in Russia, the usual procedure, but boarded directly onto the second ship. Questions like Who has control of nuclear weapons? kept coming to mind.

In Istanbul we were able to sandwich CNN International News between tours of mosques and the Grand Bazaar. Shortly before we departed, Gorbachev spoke on TV about his ordeal. He looked older, but was free, and our minds were free of worst-case-scenario fears as we returned home.

I’ve had the pleasure of helping you find books at the library. (I’m telling you, folks, this place is crawling with talented writers.) What kind of books do you read a) for enjoyment, b) for research into current children’s books and c) for research on your own projects?

You generally help me with children’s books—resources for a potential project as well as titles or author names I’ve forgotten. For juvenile and adult reading and writing projects, I tend toward science, especially natural history, and poetry. I also enjoy fiction involving other cultures or subcultures such as Snow Flower and the Secret Fan, The No. 1 Ladies’ Detective Agency, Jhumpa Lahiri’s short stories, A Texas Trilogy of plays by Preston Jones, and I go through art and photography phases.

I got this question from my interview with Vaunda Micheaux Nelson, whose great-uncle started a bookstore with 5 books, so I’m going to call it the Professor’s question: if you were going to start a store (or a library) with 5 books, which 5 would you choose?

The Complete Works of Shakespeare and an OED are certain. Perhaps Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath and Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird. I’d consider Zen Shorts by Jon Muth or Aesop’s Fables that would be accessible to children and adults. This is an interesting exercise, but with e-readers now one might have to answer, Which 250 books would you include?

What are some of your favorite New Mexico books, for children or adults?

When I first moved to New Mexico’s ranch country I went to the monthly bookmobile to learn about my new home. My favorite books still are from that time. Almost anything by Frank Waters, Bless Me Ultima by Rudolfo Anaya, We Fed Them Cactus by Fabiola Cabeza de Baca, No Life for a Lady by Agnes M. Cleaveland, The Sea of Grass by Conrad Richter, Wind Leaves No Shadow by Ruth Laughlin, Zuni Breadstuff by Frank Hamilton Cushing, The Blessing Way and Listening Woman by Tony Hillerman. For children—In My Mother’s House by Ann Nolan Clark and Byrd Baylor’s books, especially when her words are paired with Peter Parnall’s art. Even though all of the latter aren’t strictly of New Mexico, they epitomize my feelings for this state.

Thank you, Katherine!

Read Kirkus’s review of What’s for Dinner? here. Hint: star!

This is part 3 of a series of interviews with New Mexico children’s writers for the state centennial in 2012.

Uma Krishnaswami’s The Grand Plan to Fix Everything (Atheneum, 2011) was one of my favorite books of 2011, and if I were compiling a list of children’s books that read as master classes in setting, characterization, plot, and all-around niftiness, it would be on that one, too.

When Dini’s family moves from Maryland to India, she has to leave her best friend behind, but there’s one bright spot: maybe, with a little detective work and some Bollywood-style luck, she can discover what in the world is going on with her favorite movie star, Dolly Singh.

First question: I loved The Grand Plan to Fix Everything! Okay, that’s not really a question. First real question: There are so many threads in TGPTFE; what came to you first? How do you work out a plot structure like that without driving yourself to distraction?

that’s not really a question. First real question: There are so many threads in TGPTFE; what came to you first? How do you work out a plot structure like that without driving yourself to distraction?

Dini and her family came first. Then Dolly, and finally the details of the place. My deep, dark secret is that I do in fact drive (write) myself to distraction, adding more and more until I can practically feel the kitchen sink in my hands, ready to fling onto the heap. At that point, I set the sink down, calm myself, and force myself to look at what I have on the page. That helps me decide what really belongs and what was just a distraction. Distractions can often be lovely and alluring. Oh, look! A diamond ring! A cell phone! I should put them in.

Hmm. Then I have to decide which one needs to play a central role, and which one can be an aside, part of an event that is part of the story but need not be onstage.

I had a few other elements in earlier versions—bags of noodle soups, a garden statue, a brother. Oh, yes, some of the scraps in that kitchen sink needed to go right into a compost pile.

If all that sounds messy, it is. Writing is not a tidy task. If a story falls into place too easily, I know that I simply haven’t worked hard enough at it.

I’m always interested in what writers have to say about creating voice. I’ve heard you talk about the voice in TGPTFE, which is, to my mind, one of the most memorable voices in a work for middle grade fiction this year, and one of my favorite elements of the book. Can you say something about how that voice manifested itself to you (or however you might like to put it!)

It sounds cliched, but that voice, and most of chapter 4, came to me in my sleep. (C.L.–Does that mean I should spend more time sleeping?) I’d gone to bed with a rather tangled storyline emerging in my mind and no idea how I was going to bring it to any kind of conclusion. Dini and her parents, Maddie and Dolly, were all part of this tangle. I woke up early in the morning—definitely past midnight—with that very brief chapter resonating in my mind. I wrote it down at once, as fast as I could. A few words changed, but all that text remained pretty much as it showed up. That does not happen very often to me, so I knew it was a gift from the universe of story, and I needed to accept it without question.

Some of the most memorable characters are adults—I’m thinking of Lal, poor Chickoo Dev, Dad with the nifty sayings, and of course Dolly herself. How do you approach writing adult characters for a young audience?

I didn’t even think of that in early drafts. I just wrote them as they showed up. In revision, I knew I’d need to pull Dini’s story to the foreground. As she inched slowly into a central role in the story of her own life, the adult characters assumed their own roles. Some of them were absurd, some were eccentric in a loving kind of way. There are no villains in this book, something else I was conscious of as I wrote. It wasn’t intentional—it just happened that way.

Now that you say that, I think it’s pretty refreshing to have a compelling story, one that feels like it has high stakes, without having a villain. After all, we don’t encounter villains every day, but we all have plotlines we want to see through.

In part 2 of your conversation with Joanne Rocklin (1), you say that when you get stuck with writing, you read and absorb the voices of characters and the narrative choices of the writer. What are some books that you’ve absorbed in this way? Who are some of your favorite writers to read when you’re looking for that kind of inspiration?

In general when I get stuck I try to read work that is different from anything I’m writing. I read poetry, or essays, or any kind of writing in which the words matter. A Natural History of the Senses by Diane Ackerman, for example, is a book that can stir my words back to life when they feel sluggish. For The Grand Plan to Fix Everything I found myself wanting to go back to the books that made me first want to write, years and years ago. I revisited P.G.Wodehouse’s marvelously crafted escapades in the idealized England of his books, and R.K. Narayan’s utterly brilliant Malgudi Days, in which the writer turns a sort of fiercely loving eye onto a tiny, idiosyncratic fictional rural community in India. These are not of course written for children, but they gave me ways to position myself as I wrote my book. They gave me the confidence to create the kind of closed world I was after for my story. They helped me to get a running start again, at times when I felt myself flagging.

One of the delights of this book is the way you present India, from its speedy India Post to its Dreamycakes Bakery and, of course, monkeys in the water tank. Much of this is based on the Bollywood conception of India. How do you go about creating such a vibrant setting for a primarily American audience?

Let me be very clear. The town of Swapnagiri does not exist. But the Nilgiris (Blue Mountains) do, and so do the flowers for which they’re named. The monkeys, the hill roads, the mists, the tea gardens are all drawn from places I know in India with a sort of cinematic shimmer added to them. The shimmer comes from Bollywood of course, but the places, including Sunny Villa, are straight from my very early childhood.

Can I ask the same question you asked a group of writers: Who was your audience when you wrote this book?

I suppose my first audience in early drafts was my younger self, the 10- or 11-year-old self who still exists in my mind. Then my wonderful writing group was my audience. They interrogated the work fairly thoroughly. (Vaunda Nelson and Katherine Hauth are both members—I imagine you might talk to them as well about their new books (2).) Much later in the process, I became more aware of a kind of hypothetical young reader. I’d test iffy passages against the perceptions of this imaginary person, who was fairly critical and wouldn’t put up with any self-indulgence. I trust my reader, however, to stick with me even when I’m not connecting all the dots. That way lies tedium. And in the end, I think that worked, judging from letters I’ve received so far from real young readers who have read and enjoyed the book.

The writing life: that phrase conjures images not just of writing, but of talking about writing, teaching writing, writing about writing. You do all of those! It seems to me like there must be a kind of feedback loop going on. How do all of these different activities influence one another in your experience?

They keep the writing conversation alive for me. Talking to students, to my writing group, to colleagues, and writing about writing all allow me to consider my own work even when I’m taking a break from it. They keep the work in my mind but in an indirect way. When you look at something directly for too long, you can’t always see the patterns in it. Looking away and talking about the craft in a conceptual, even theoretical way, allows me to see my own work anew when I return to it.

Here’s something that’s funny and humbling all at once. I’ve often had the experience of writing a critique letter to a student and feeling satisfied. Feeling as if I’ve given the manuscript my best and closest attention. I’ve found the strengths. I’ve identified work that needs to be done. Then I go back to my own work in progress, and wham! Every single point I made about that student’s work is right there, staring me in the face, only I couldn’t see it before. I am convinced that the act of teaching makes me a better writer.

On your website, you list “20 writing tips I wish I’d heard 20 years ago.” If it’s not too much to ask, is there a 21st?

Yes. Here it is:

You don’t have to put everything on the page. Leave room for the reader to create meaning.

That’s a whole conversation in itself–how readers create meaning. It’s especially interesting when the readers are children. I remember hearing Catherynne Valente say, in response to criticisms that The Girl who Circumnavigated Fairyland was too complicated for children, that kids are used to living in a world in which so much of what the encounter is slightly beyond them, and they’re very adept at putting together what they do understand into a personal comprehensible whole.

This is part of a series on New Mexico children’s writers to celebrate the centennial. Have you ever thought about writing a book set in New Mexico? What are some of your favorite NM books, children’s or adult?

I’m growing a story set in New Mexico, but I can’t say much more than that. It’s a novel, and it’s half-written at this time. Talking about it may make the poor thing evaporate, so I won’t, other than to say it takes me a long time to work a setting into my system sufficiently that I feel I can write it with any confidence. If I live long enough I hope someday I can do a New Mexican setting justice.

Favorite NM books—oh there are so many. Of course Bless Me, Ultima by Rudolfo Anaya, but also Willa Cather’s work, and N. Scott Momaday’s House Made of Dawn, just for starters. Among children’s books, I love Luci Tapahanso’s deceptively simple Songs of Shiprock Fair with its wonderful illustrations by Anthony Chee Emerson. More recently, I’ve enjoyed reading Diane Stanley’s middle grade novel, Saving Sky.

That’s two votes for Willa Cather, not that it’s a contest. But I’ll add mine to that, as well as to Songs of Shiprock Fair. Thank you, Uma!

1. You can read Part One and Part Two on Uma’s blog.

2. I did indeed interview Vaunda! And here it is. Watch for an interview with Katherine Hauth in the near future.

This is part of a series of interviews with New Mexico writers for the 2012 centennial.

In Caroline Starr Rose’s debut, May B., May Betterly is sent to help reluctant prairie wife Mrs. Oblinger with the housework in a Kansas soddy and earn a little money for her family. She’s not happy about it, and she’s even less happy when she discovers she’s been abandoned and left to fend for herself in the cold Midwestern winter with a bit of sourdough, some apples, and herself for company. Here, Caroline talks about bearing the mantle of Poet, her love for Laura Ingalls Wilder, and writing about conflict.

- To begin with the obvious: May B. is a historical novel in verse, specifically in 151 numbered poems. I remember hearing you talk about language in both rhyming picture books and verse novels, and your love of language comes through on every page. What draws you to write in verse, and in historical fiction, and why do you think they work well together?

Thank you, Rebecca! I’ve always been nervous of the weightiness the words poetry and poet carry. A few years ago at one of Darcy Pattison’s revision retreats, we participants were asked to talk about what we’d published and/or written. When I shared I’d sold a few poems and was querying a historical verse novel I’d just finished, Darcy said, “Sounds like you’re a poet.” I can’t tell you how hearing that terrified me!

Verse is something that found me. When I started working with May B., I was frustrated at the distance I felt between what I wanted to convey and what was actually on the page. I spent some time looking back over first-hand accounts of pioneer women and noticed in their writing the spare word choice and the matter-of-fact presentation of events (some mundane, some heartbreaking). With this in mind, I immediately wrote what is now poem 2 in May B., choosing to let the words and May’s bleak situation speak for themselves. The experience was magical; I’d felt like I’d found some hidden formula to finally tell the story in the most honest way possible.

As for historical fiction, using verse can certainly speak to the setting and character’s circumstance. After my ah-ha moment, I understood why Karen Hesse chose to use verse for Out of the Dust: spare language suited the bare Dust Bowl landscape and paralleled Billie Jo’s whittled-down life.

I’m guessing that many reviews will draw comparisons with a) Little House on the Prairie and b) Out of the Dust. Maybe even a little bit of c) Sarah, Plain and Tall for good measure. But every work needs the chance to stand on its own merits, and May B. does that beautifully. What is it about May’s story that made you want to tell it?

I have to confess I asked my editor countless times if May B. was coming across as a Little House knock off. I lived in Laura Ingalls Wilder’s books as a girl, and I worried her stories would seep too much into mine. It’s been wonderful to see reviewers point out the parallels — Kirkus called it Laura Ingalls inspired; Horn Book described it as Little House without the coziness (yes, I’ve memorized these words like a love-sick teen) — but still present the book on its own merits.

There are a couple of reasons I wanted to write this book. Again, with a nod to Laura (we’re on a first-name basis, the two of us), I wanted to create my own strong pioneer girl. I was also fascinated by the challenge solitude would present in telling a story. Ultimately, though, I wanted to examine the concept of worth — how so often who we are becomes based on what others tell us about ourselves or on what we’re able to do. Like May, I think all of us in some way feel we don’t measure up. I hope many readers will be able to relate to — and find confidence and courage in — her story.

The contrast between limits and open spaces strikes me as a potent theme here. Physically, you’ve got poor May stuck in a leaky soddy in the middle of the vast prairie, and psychologically, she’s got vast stretches of empty time, but her dyslexia keeps her from using that time to practice the one thing she seems to want to do most. Can you talk a little about setting up conflict, and especially how that plays out in verse?

May’s name came to me before her story did. I liked the way May Betterly could become May B. and how “maybe” could speak to her perception of herself (maybe is such a wishy-washy word. It makes me think of mediocre or so-so). From this, I decided the most direct way to challenge her would be to have her long for something that would have been virtually impossible for a dyslexic child in her era: becoming a teacher.

Then there’s the external struggle for May just to stay alive. In telling a story with essentially one character, it would be very easy to just live in her head (especially with the way verse allows such close observation of a character’s mind). But I couldn’t do that. I had to keep the internal and external wound together to keep the story moving, to help May grow, and to hold onto the interest of my readers.

For me, as a reader, I love finding things that parallel and things that contrast. It was fun to examine these things in writing May B.: feeling trapped on the vast prairie, longing for the very thing most out of reach and how that shapes a person (one of Emily Dickinson’s recurring themes and has always fascinated me), light and dark, freedom and limitation…I’m not really answering your question, am I? (C.L.- I like your answer anyway!) I found verse a clear way to juxtapose these sorts of things. It leaves the reader to mull over and draw conclusions outside of what’s presented in the text.

Just one more question about verse novels: you posted on your own blog about people’s reactions to novels in verse, and I was thinking as I read May B. a second time that it has a lot to do with expectations, sort of like in visual art. People expect “verse” to rhyme, or at least to have a distinguishable meter, just as they expect a picture to represent something they can easily identify. Some of the very brief poems in May B. remind me of a piece of flash fiction by Lydia Davis–I’ve never read it, but I heard it, and it stuck in my head: “Samuel Johnson is indignant/that Scotland has so few trees.” I think that’s the whole thing. Where’s the line between verse and other forms like flash fiction?

Wow. I’ve never thought along those lines. I completely understand why someone might not see some of May B.’s short poems as verse — My ankle’s purple / those stupid boots. comes to mind. Still, that poem captures an exact moment I felt needed to stand alone. As to the line between flash fiction and verse, I’m not sure where it is! I’m curious; what do you think?

Since you asked: I think they both rely heavily on the power of images to convey multiple meanings, and to distill ideas to something very potent, almost something you can hold in your hand. I’d guess that the form is really the distinction, so maybe it’s a visual genre separation when you’re talking about that very, very brief flash fiction. But enough from me.

Okay, a little bit more from me. A lot of middle grade books center on family themes, but you’ve put May in a situation where she’s completely alone. Was that intentional, and can I therefore add it to my bibliography of books about survival?

Utterly intentional. There were days I cursed myself for trying this solitude experiment in words, as it wasn’t easy. Remember that Tom Hanks movie, Castaway? (C.L.-Wiiilson!) It fascinated me that with very little dialogue (apart from conversations that took place with Wilson the volley ball — this was brilliant, I might add) we could still come to know and care about this character and his circumstance. I’m also a huge Gary Paulsen fan and love it when readers see parallels with May B. and Hatchet. So, yes, please add to your survival bibliography!

You have a lot of resources on your blog for classroom teachers. What other books would you recommend for a teacher who wanted to do a unit on a) frontier living and b) children with dyslexia?

Prairie Song – Pam Conrad

Pioneer Girl: A True Story of Growing up on the Prairie – Andrea Warren

Dear America: Across the Wide and Lonesome Prairie – Kristiana Gregory

The only books that deal with a dyslexic child that I can think of is the Percy Jackson series. Enlighten me if you know of more!

The Hank Zipzer series; My Name is Brain Brian; Stravaganza: City of Secrets. I’m sure there are more.

What are some of your favorite recent books? Favorites of all time?

Last year I ate up Lives Like Loaded Guns: Emily Dickinson and her Family’s Feuds. A few books from this year that come to mind are Mockingbird, Stupid Fast, Between Shades of Gray, A Northern Light, and the forth-coming The Wicked and the Just. My favorite books of all time are The Count of Monte Cristo, Possession by AS Byatt, Katherine by Anya Seton, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, House of the Spirits, and The Phantom Tollbooth.

Because this is part of a centennial series on New Mexico children’s writers, let’s have a couple of New Mexico questions. (No, not “red or green?”) Have you thought about writing a book set in New Mexico? What piece of NM history (I guess I’m just assuming it would be historical) might you write about?

Wait! I must answer red or green! I’m not allowed to live here if I don’t. I vote for Christmas; if I go with only the red or green chile, I always feel like I’ve missed out.

I’d love to write a New Mexico book someday, and it would be historical. Acoma Pueblo has always fascinated me, but Kimberley Griffiths Little beat me to it with Snakerunner. Hmm…maybe the Pueblo Revolt?

Do you have any favorite books set in NM, either children’s or adult?

I’d have to say Death Comes for the Archbishop, Rio Grande Stories, and The King’s Fifth. I haven’t picked up Tortilla Sun yet (I really need to).

When will the annual SCBWI conference be held in Albuquerque? (You don’t have to answer that one, but wouldn’t it be nice?)

Great question! Mountains, deserts, turquoise skies, the aforemetioned chile — who wouldn’t want to come here? Come on, SCBWI.

Thanks, Caroline!

Visit Caroline’s website here. And if you’re in New Mexico, Caroline will be doing an event at Alamosa Books in Albuquerque. See here for more information.

In 2012, New Mexico celebrates its statehood centennial. This will be the first of a year-long series of posts on writers and books in New Mexico.

I was sitting geekily in my pajamas watching the ALA Youth Media Awards announcements in 2010, fully expecting to see Rebecca Stead and Jerry Pinkney win the Newbery and Caldecott, respectively. But the thing that made me choke on my toast was this: the winner of the Coretta Scott King Author Award was Vaunda Micheaux Nelson for Bad News for Outlaws: The Remarkable Life of Bass Reeves, Deputy U.S. Marshal (Lerner, 2009). Ordinarily, I wouldn’t have trouble eating and reading at the same time, but this occasion was noteworthy because I work with Vaunda, and because I knew that she was attending ALA Midwinter as a member of the 2011 Caldecott committee (1).

I was sitting geekily in my pajamas watching the ALA Youth Media Awards announcements in 2010, fully expecting to see Rebecca Stead and Jerry Pinkney win the Newbery and Caldecott, respectively. But the thing that made me choke on my toast was this: the winner of the Coretta Scott King Author Award was Vaunda Micheaux Nelson for Bad News for Outlaws: The Remarkable Life of Bass Reeves, Deputy U.S. Marshal (Lerner, 2009). Ordinarily, I wouldn’t have trouble eating and reading at the same time, but this occasion was noteworthy because I work with Vaunda, and because I knew that she was attending ALA Midwinter as a member of the 2011 Caldecott committee (1).

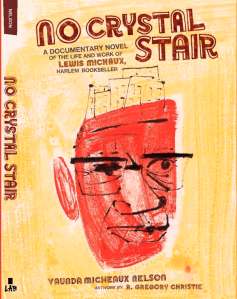

There was a slight kerfuffle at the library when Vaunda returned from the conference. I think we’re all still kerfuffling inside two years later, because Vaunda never stops being amazing, whether it involves dressing like a pirate to advertise summer reading or writing a new book, the truly remarkable work of YA fiction, No Crystal Stair: A Documentary Novel of the Life and Work of Lewis Michaux, Harlem Bookseller (Carolrhoda Lab, 2012). I know that not all subtitles can contain the word “remarkable” but I really think this one should. When you see the words “documentary novel,” don’t think that it’s along the lines of Deborah Wiles’s Countdown. This is something completely different. And check out that cover by R. Gregory Christie, who also did the interior illustrations.

Lewis Michaux opened and ran the National African Memorial Bookstore in Harlem for nearly forty years, beginning in the Depression. He made this decision in a time when the opinion of most white bankers was that a bookstore that sold books by and about black people was a sure bet for failure. Michaux proved them wrong and made history in the process, along with friends like Langston Hughes, Malcolm X and Nikki Giovanni. Michaux is Vaunda Nelson’s great-uncle.

No Crystal Stair is written as oral history, based on interviews Vaunda did with family members and people who knew Lewis Michaux, and research in sources as diverse as newspapers, FBI files, and church newsletters.

First off, the epigraph you chose (“They call me the professor and I say, ‘You’re right. I professed to do something and I did it.'”) really gives a sense of who Lewis Michaux was–his way with words, and his incredible determination. That’s worth framing! Is that one of your favorite quotes from your great-uncle?

This is certainly a favorite quote for the reasons you have given. I also enjoy the way Lewis sometimes makes a word mean what he chooses — in this case “professor.” But there are so many memorable quotes from my uncle. This was part of the fun in my journey through this project.

Although this story is fictionalized, you’ve taken care to ground it in real events. One of the first things we see Lewis do is steal a bike (and later on he goes “pig picking”), so it’s clear to the reader that you’re not setting him up as a conventional hero. Talk a little about his character, and what made you want to tell his story.

It’s true that Lewis wasn’t heroic in the way the Bass Reeves was. I can’t describe him as “right as rain from the boot heels up.” But in many ways I can say he was a “square shooter.” He spoke his mind. You knew where you stood with him. As my mom once said, “He wasn’t two faced like some.” Although there are aspects of Lewis’s character that are not admirable, the more I uncovered about him, the greater my passion grew for him and his story. He was a person worth knowing.

I’ll say! I love the photographs of Lewis with various prominent people of the time.

Like Who Will I Be, Lord? (Random House, 2009), this is a family history project. The form you’ve used here is particularly interesting, though: it’s an oral history-style “documentary novel” made up of hundreds (I didn’t count, but it must be hundreds) of pieces attributed to dozens of viewpoints: you’ve got family members, bookstore customers, newspaper articles, FBI files, and of course Lewis himself, as well as many others, all weighing in a different times with their opinion, sometimes despairing, most often awed, about Lewis and his bookstore. How does compiling a work this way change how you see your great-uncle?

It’s looking at the whole person, or attempting to. The process made me dig deep and see more. It’s one of the things I admire about Marilyn Nelson’s Carver: A Life in Poems. She not only informs readers about Carver’s brilliance and accomplishments, she leaves us with the essence of the man, the nature of his spirit. I attempted to do this with No Crystal Stair. I hope I succeeded.

Lewis Michaux was a dedicated bookseller. He started his business at a time (around the end of the Depression) and in a place (Harlem) that seemed to be inimical to bookselling, and yet he was a great success. What is the role of the bookseller today, when we’re (still) dealing with proving the relevancy of books and reading?

It’s no secret that independent booksellers are challenged in today’s business environment. First it was the big chains, now it’s online competition, too. Independent stores have one thing over the large chains — their stock, which includes those little gems, those obscure titles that stores like Barnes & Noble generally don’t carry. But now, the little gems (including out-of-print titles) are available through online retailers like Amazon. This eliminates the edge that small stores once had. Downloadable books, too, are challenging the print industry. But what the mom-and-pop bookstores still have to offer are knowledgeable, passionate staff and real, one-on-one customer service. What they have to offer is heart. Also there’s nothing like the experience of browsing bookstore shelves and discovering those obscure titles, pulling a book off the shelf, holding it in your hand and turning the pages. Browsing online can’t compare. The future? I don’t know. I admit that I’m nervous about what may become of brick-and-mortar neighborhood bookstores. I try to patronize these little shops to help keep them around.

Lewis started his business with 5 books. If you had to pick 5 books to start a bookstore (any kind of bookstore), which 5 would you choose?

This is one of those impossible if-you-were-marooned-on-a-desert-island questions. (C.L.-Sorry!) Lewis’s five books were basically what was available to him and not specifically selected. I suppose if I were starting a bookstore it would probably be focused on youth. And if I were choosing titles I might consider Sylvester and the Magic Pebble, To Kill a Mockingbird, The People Could Fly: American Folktales, The Polar Express, Pinocchio, Charlotte’s Web, Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry, Flossie and the Fox, The Dream Keeper and Other Poems, Frog and Toad are Friends, Eloise, You Don’t Know Me, The Borning Room . . . Obviously, choosing would not be easy. But it would be fun to see what five titles young people might pick.

That would be a great question for kids. Do you have any of your great uncle’s books? (I mean, ones that belonged to him and that he personally read.)

I have two books that he gave me when I visited the store in 1968 — The Masquerade by Oscar Micheaux (a historical novel) and a copy of the King James Bible. I know his son, Lewis Jr., has many books that belonged to his father.

The flyer for the closing of the bookstore lists “hundreds of children’s books” among the stock to be sold off. Do you know what any of those children’s books were?

I can’t know for sure, but I suspect books by authors like Gwendolyn Brooks, Julius Lester, Arna Bontemps, Sharon Bell Mathis, Ann Petry, Rosa Guy, Mildred Taylor, Lucille Clifton, Tom Feelings, Virginia Hamilton, and of course, Langston Hughes were among them.

The line from Alex Haley (“When an older person dies, it’s like a library burning to the ground”) seems like it could have been the inspiration for this entire work, trying to capture the voices of people who knew Lewis while they are still here. Did Lewis write much himself? And do you have plans to write about more of your family history?

Lewis recorded his philosophies and ideas through his own brand of poetry, much of which is in No Crystal Stair, but I don’t know that he wrote extensively. I love exploring family history and, if a new story or individual taunts me to pursue, I’ll follow. I’ve been kicking around a story about my grandmother Sinah, who married Lewis’ brother Norris. We’ll see.

Thank you Vaunda!

Vaunda Nelson is the author of ten books. She’s also a children’s librarian, and in 2012 she is the official New Mexico Centennial Children’s Writer.

1. Betsy Bird captured this moment on video here.

Here is School Library Journal’s interview with the March 2010 cover girl.

And her speech in The Horn Book.

Awards for children’s books have a long an illustrious history, not to be recounted here. You have heard of the Newbery. You have heard of the Caldecott. Have you heard of the Sibert? Ah! That is an award for informational literature for children, otherwise known as nonfiction. Typically it goes to beautifully produced trade nonfiction like Kakapo Rescue: Saving the World’s Strangest Parrot (Houghton Mifflin, 2010) by Sy Montgomery, photographs by Nic Bishop.

Montgomery and Bishop can fairly be called superstars of children’s nonfiction. Montgomery has written eight well-reviewed books for children, many based on her work for adults. Bishop’s trade books are so well-conceived that they have titles like Nic Bishop Frogs (Scholastic, 2008). Two of his other trade books, one by Montgomery and one written by Bishop himself, have won Sibert honors. But Bishop has another line, in what his website calls “books for schools,” but what we librarians call series nonfiction. He’s done dozens of these books, with little fanfare.

Pause for a definition: trade nonfiction you can buy in a bookstore; series nonfiction is produced specifically for the school and library market, is often linked to curriculum standards and reading levels, and can generally only be purchased through library vendors. They have what is called “library binding,” and often have nice wipeable covers to erase the stickiness of many enthusiastic and grubby hands.

So why is it that Bishop’s trade books can win awards, but not his series books? I haven’t examined them, and I’m not saying that they should win awards. I’m not saying that a series book will never win the Sibert. I’m saying (clearing my throat and puffing up my chest) that, darn it, series nonfiction deserves an award of its own. Trade nonfiction has the Sibert. I humbly suggest an award for series nonfiction:

The SNibert. Pronounced “sny-bert” with a long I. (And keep in mind that ALA can afford professional designers, wheras I cannot.)

examples of the “yucky science” trend that’s been going for a few years. Many of these series featured material and presentations that would not only draw young readers in but would also provide solid material for reports or science fairs, essential in libraries that can’t buy materials that fill only one need. Series such as Enslow’s “Bizarre Science” from Spring 2011 and Capstone’s “Nasty (But Useful) Science” from fall 2010 come to mind.

CP: I’m particularly impressed with how publishers are taking much-covered topics and presenting them in new and exciting ways. Whether using a graphic novel format for biographies, mixing science and science fiction, or listing websites to interactive online materials, series nonfiction is responding to readers and the changing times. The series that have been pushing the envelope have by and large been my favorites in recent years.

ETV: This is really a question for publishers, but from my perspective I would point out turn-around time—these books that are shorter and often rely on stock images and existing research can be produced quickly. And of course there is the granularity issue mentioned above—series nonfiction often covers the same material in multiple books that trade books cover in one volume. An easy answer here would be to deride the quality of this genre, but over a few years at Series Made Simple I got to see many examples of quality series nonfiction, so that generalization no longer holds true, if it ever did.

CP: Oh boy, a lot. The bindings and designs are usually different. The formats are consistent across volumes. They are produced as a set. I could go on and on about differences, but a lot of the stronger series share editorial qualities with excellent trade books: great text and eye-catching and edifying visuals.

How can a librarian judge a quality NF series? What makes a series stand out?

ETV: It’s no longer necessary for them to judge, as they can pick up a copy of Series Made Simple! But, if they must decide all on their own, the qualities they should bear in mind are the same as for any nonfiction book. Does it cover a subject my library needs at the level at which my patrons need it? Is the research thorough and accessible, including, for example, a quality index? Is the presentation engaging? Are photos and other illustrations well reproduced, relevant, and accompanied by informative captions? If the publisher is touting an online complement to the print material, is it of quality and will it last? If there is a bibliography, it should show that the writer researched using more advanced materials than other series nonfiction books, though of course the further-reading list can suggest those materials. If the library or school must adhere to certain standards, it is important that the series meets those, and a publisher should be able to confirm whether their materials were written, for example, in accordance with common core standards. Many standards emphasize the importance of primary sources and the use of these is thankfully becoming more common in children’s literature.

CP: A clear and engaging design, helpful and interesting visuals, strong back matter and/or additional resources, factual accuracy, and, of course, great writing are all important things to look for when evaluating a nonfiction series.

And now, the question that’s been on everyone’s mind (for at least ten minutes): Who would be your top contender for the SNibert medal this year?

ETV: My favorite-ever series didn’t cover science—it was Compass Point’s

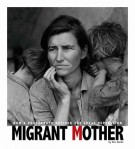

“Captured History” from spring 2011. All four books in this series were gorgeous and meticulously researched, but the one that I still think about is Don Nardo’s Migrant Mother: How a Photograph Defined the Great Depression. This stunning book looked at the background of two women whose very different lives became intertwined—Dorothea Lange, the famous depression-era photographer, and Florence Owens Thompson, her most famous subject. It describes the years leading up to the heartbreak depicted in Lange’s searing image and the aftermath of the photograph for both women.

CP: I hate to have to choose just one, but because I am a fashion buff and a history nerd, I really enjoyed reading Twenty-First Century Books’ “Dressing a Nation: The History of U.S. Fashion” series. The Little Black Dress and Zoo Suits: Depression and Wartime Fashions from the 1930s to the 1950s is particularly fascinating and what a great cover!